Learn how Zoom dysmorphia is impacting your patients

With many still working from home in some capacity, virtual meeting technologies have pushed people to look at their reflection much more than before the pandemic. The problem is that using front-facing cameras so often can distort our self-image. To learn how to combat these effects, we talked with dermatologist, Arianne Shadi Kourosh, MD, MPH from Massachusetts General Hospital.

What is Zoom dysmorphia, and how has the pandemic contributed to it?

Throughout the pandemic, many of us have been spending hours a day on video calls, which can impact how we think about our appearance. We’re viewing ourselves much more frequently, for longer periods of time and from strange angles with technology, leading many to think negatively about their appearance, focus on perceived flaws, and seek cosmetic care. With the term Zoom dysmorphia, we hoped to spark a discourse in the medical community about a phenomenon that we were observing unique to the living conditions of the pandemic, which we were concerned may trigger or worsen body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) in our patients. However, it is important to make the distinction between a term like Zoom dysmorphia that is useful for education and awareness—from the actual medical term such as BDD, which has its own criteria for diagnosis for which we would refer to a mental health professional.

What conversations should dermatologists have with their patients regarding BDD/Zoom dysmorphia?

Our study surveyed dermatologists across the country and found that the shift toward remote work and videoconferencing due to the pandemic has led people to scrutinize an unflattering and distorted image of themselves on screen and seek cosmetic procedures as a result. Dermatologists should be aware of this trend as well as the limitations of webcams and should encourage patients to have a discussion with a medical professional if concerns for appearance arise.

It may be helpful to remind patients to reconnect with the aspects of self-perception that grounded them before the pandemic, such as turning off front-facing cameras when possible and reconnecting with supporting relationships and interactions that affirm self-perception. It is of utmost importance that individuals consult a board-certified physician that cares about health and well-being and will tell them honestly if a procedure is in their best interest. Our hope is to encourage a discussion in the community of aesthetic medicine that will help us as physicians to be prepared to address this issue so we can take care of our patients as a whole person and support mental health and wellness.

What trends in patient concerns and procedures are dermatologists/aesthetics specialists seeing in their practice post COVID?

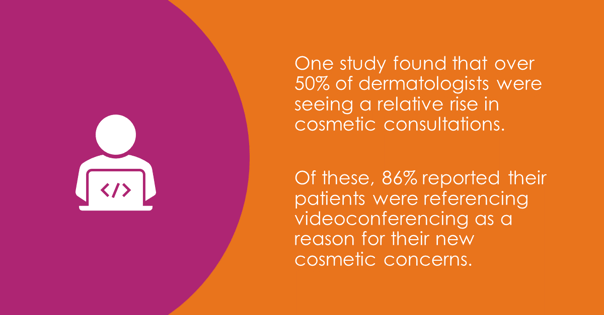

In the midst of the pandemic, we surveyed over 130 members of a national organization of dermatologists and found that over 50% of dermatologists were seeing a relative rise in cosmetic consultations.2

Of these, 86% reported their patients were referencing videoconferencing as a reason for their new cosmetic concerns. The most common patient concerns included features from the neck-up, such as upper face wrinkles (77%), dark circles under the eyes (64.4%), facial dark spots (53%), and neck sagging (50%), all of which may be exacerbated by camera angle, focal length, and shadow distortion.

Neuromodulating agents, filler injections, and laser treatments were the most frequently requested cosmetic procedures. For those who were accustomed to receiving these treatments every few months prior to the pandemic, there was noticeable concern for return of dynamic wrinkles following months without treatment, especially in setting of videoconferencing where they were forced to look at them in an unnatural way for hours on end. Additionally, squinting and focusing on screen during videocalls can exacerbate dynamic wrinkles, leading many to be unpleasantly surprised by their facial lines seen on screen. Similarly, interest in skin tightening procedures of the neck also spiked during the pandemic, with concerns for neck sagging made worse by unfortunate camera angles and focused attention during video calls.

Wellness tips to share with patients working remote

- Assess your technology: Consider using an external, high-resolution camera for quality video and adding a ring light to control how you illuminate your face, which will also improve how you appear on camera.

- Adjust your camera: Try positioning the screen a further distance away from your face and keep the camera at eye level, which can help to minimize the distortion of the camera and improve appearance.

- Protect your mental health: Find opportunities to reduce the amount of time spent looking into a front-facing camera by turning off your video on calls when it is not required. It can also be helpful to limit social media engagement. Since photo editing is so pervasive on social media, it’s unhealthy to compare your own distorted images from front-facing cameras to edited and augmented photos posted online. It may also help to talk with a mental health professional, who can help a person take a healthier approach to their appearance and offer strategies for redirecting ones focus away from perceived physical flaws.

- See a board-certified dermatologist: If you’re concerned about your appearance, see a board-certified dermatologist, who can help identify whether a problem truly needs aesthetic intervention and if so, can recommend appropriate products or treatments to help you look and feel your best.

About the author

About the author

Arianne Shadi Kourosh, MD, MPH from Massachusetts General Hospital is a Director of Community Health, Founding Director, Pigmentary Disorder and Multiethnic Skin Clinic and a Assistant Professor, Harvard Medical School.

References

- Rice SM, Graber E, Kourosh AS. A pandemic of dysmorphia: “Zooming” into the perception of our appearance. Facial PlastSurg Aesthetic Med. 2020;22(6):401-402. doi:10.1089/fpsam.2020.0454

- Rice SM, Siegel JA, Libby T, Graber E, Kourosh AS. Zooming into cosmetic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic: the provider’s perspective. Int J Women Dermatol. 2021;7(2):213-216. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.012